Just as things go wrong on a large scale, for example, the Berlin Airport or the Elbe Philharmonic Hall, every project runs into the danger of overshooting the set conditions. The control of projects is always a gamble on the shoulders of the project leaders due to the many influencers, the rarely defined power structures, and the vague specifications. They may have the mandate to hold the steering wheel in their hands, but the steering angle is severely limited by the stakeholders’ diverse and even conflicting concerns. In the end, project managers are the executing, extended arm of the contracting parties, who micromanage vital decisions. The most significant burden is primarily the fuzzy requirements that keep changing over time. However, to simplify the management of the initiative, leaders do not try to identify and consider the essential factors. They conclude based on simple-minded contingency*.

*”Contingent is something that is neither necessary nor impossible; what can be as it is (was, will be), but is also possible in other ways. The term thus denotes what is given (what is to be experienced, expected, thought, fantasized) with regard to possible otherness; it designates objects in the horizon of possible modifications.”

(see Social Systems, Niklas Luhmann)

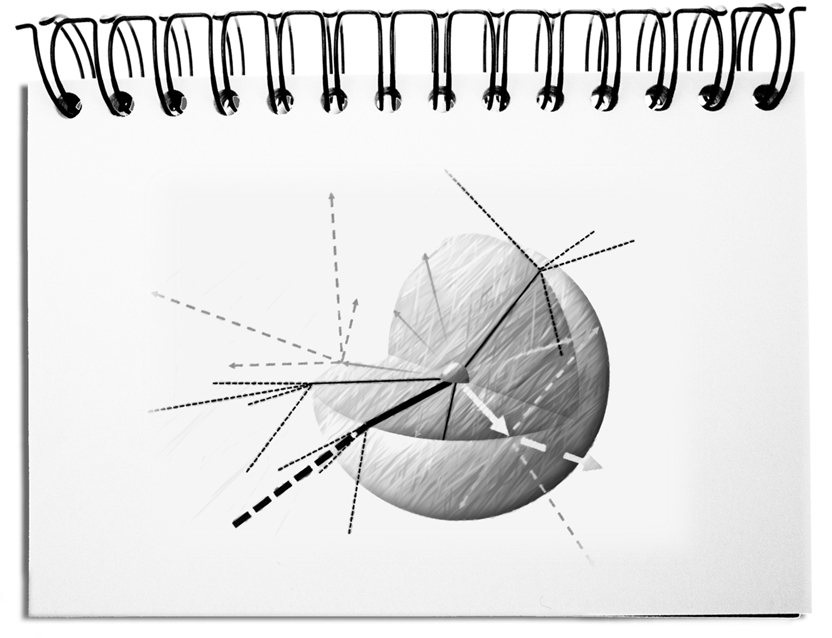

The description of the situation becomes one-sided when only one cause and one consequence are considered. While it is impossible to identify ALL influences and effects, the blinkered shielding of adjacent possibilities inevitably leads to delays and other disadvantages. In overcoming the limited viewpoints, the following aspects will help.

- Overcoming Maslow’s hammer

With the growing labor division, the law of the instrument has emerged – i.e., if someone has a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When looking at a project, the financier sees only the monetary, the buyer the procurement, and the HR people the personnel aspects. The decision-makers have the whole picture in mind. However, they are also driven by their priorities – e.g., to generate savings, build reputation, and get through the week without stress. For overcoming one’s bias, the mindset supports Anything is possible. To find the given possibilities, it helps to let go of what is taken for granted, question existing structures, and think without limits. - Describing the focal point

The starting point for the treatment is the printable situation description. It is always good to focus on one issue, otherwise, the solution will be diluted or even impossible. If, for example, the focus is on a project delay, then the generalized discussion of the deficits in the project work is of no use.

In addition to the factual points (i.e., where happens, what, when, how, and who is involved), we recognize by the stakeholders’ intentions, who have different influences on what is happening what needs to be monitored. With their description, the project leaders show their mental states through the formulations and emphases – e.g., what is important to them; what they dislike; what they need. - Understanding, not analyzing causes

The likelihood that a concrete situation will result from a single cause is low. Usually, several circumstances are involved. However, the law of the instrument dictates that causes are sought only within one’s domain. Although these limitations are clear to unbiased observers, decision-makers are driven by the need to take care of situations. This is best done by assuming a monocausal case. Solving one cause does not eliminate the problem.

Even if not all causes will be identifiable, it is crucial to take the risk to look beyond one’s nose since neighboring causes contribute to the issues. On the one hand, the look through the functional glasses is recommended: e.g., development, procurement, production, and selling and, e.g., personnel, accounting, and IT. On the other hand, considering the influences of technology, culture, organization, and economy provide additional leverage points for clarification. In any case, you must not analyze the particular areas, i.e., putting them in-depth under the microscope. It is enough to understand the causes. - Anticipate consequences instead of elaborating in detail

Due to the affected areas and the various stakeholders, several consequences are always to be expected. However, since the actual effects do not appear until the future, we can only guess the effects. Here again, Maslow’s hammer impacts, which leads to the fact that we only see developments in our sphere of influence – e.g., the financier only finds monetary (dis)advantages.

Since the future is only manifesting later, you should not cross your bridges before coming to them. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to anticipate the neighboring consequences. To be able to react to significant futures, we develop scenarios with possible upcoming circumstances. These alternative designs of the future make statements, for example, about companies, people, business development, available technologies, the development of the economy, society, and the environment. Again, the aim is not to provide detailed descriptions but to anticipate adjacent consequences so that they are not ignored.

Bottom line: The key message of this article is to respond to a difficult case with multi-causal solutions that take advantage of existing possibilities. We never deal with simple cause-and-effect relationships. Our perception is an additional burden due to the Maslow hammer that prevents from seeing more than we usually master. A tricky situation always has multiple causes and generates many consequences that we do not have in mind. To conclude unilaterally does not offer approaches but creates trigger for follow-up problems.